The Two Coronations of the Previous King Charles

On 01 January 1651 the 20-year-old Charles II was crowned King of Scotland at Scone Palace in Perthshire. It was not an enjoyable experience, and Charles chose never again to return to Scotland. His father had been beheaded in Whitehall two years earlier, and to gain the support of the presbyterian Scots in the Civil War, Charles had been obliged to swear to uphold the Solemn League and Covenant. This committed him to abolishing the rule of bishops in the Church of England, a pledge which we knew, from clear and demonstrable reasons, that he hated in his heart … our sin was more than his. (Scots Commissioner Alexander Jaffray.)

The ancient ‘Honours of Scotland’ – a crown, sceptre and sword of state – were smuggled out of Edinburgh Castle for the ceremony. They were later wrapped in seaweed and buried at Kinneff Church to keep them out of the hands of the English. The Stone of Scone had already been looted 350 years earlier by Edward I, ‘Hammer of the Scots’.

During the ceremony Charles was subjected to a harangue from Robert Douglas about the need to avoid the sins of former kings [which] made this a tottering crown … [otherwise] all the well-wishers to a king in the three kingdoms, will not be able to hold on the crown, and keep it from tottering, yea from falling … [Should Charles disregard the Covenant, his subjects] may and ought to resist by arms.

With friends like this, it is no surprise that Charles headed in the opposite direction from Scotland after defeat at the battle of Worcester. He escaped to France and became increasingly despondent as Providence seemed to favour Oliver Cromwell, who had never lost a land battle. However, there was no agreement as to exactly what form of republican government should replace the monarchy, and when the Lord Protector died in 1658 there was only the inadequate rule of his third son Richard (‘Tumbledown Dick’), who lacked his father’s charisma, or influence with the New Model Army.

Charles II returned from exile in May 1660. He was the last British monarch to have two coronations, the second being deliberately planned for 23 April 1661, St George’s Day. He was also the last to revive the old tradition of the Coronation Eve cavalcade, carrying the monarch from the Tower to Westminster. He was acutely aware of the importance of playing to English monarchical traditions, tying him to earlier glories like the magnificent processions of Elizabeth I, and the route was designed by John Ogilby as a visual parade of propaganda. (Jenny Uglow, ‘A Gambling Man’ p115)

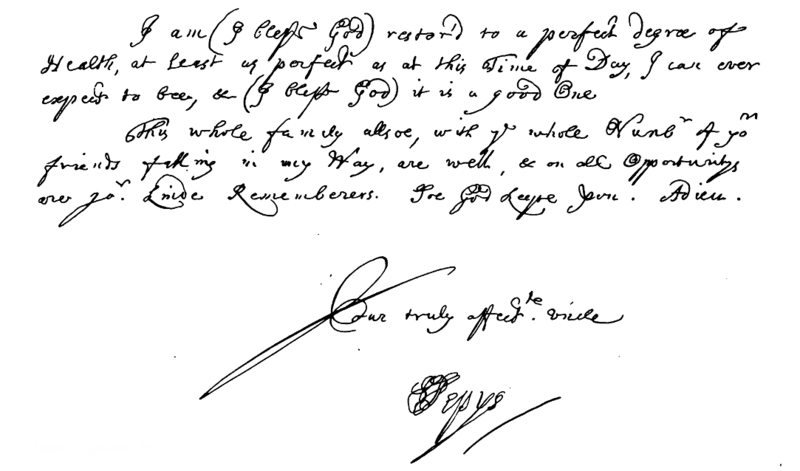

The aldermen and livery companies of the City of London paid a huge sum, £10,000, for four triumphal arches a hundred feet high. Each symbolised an anticipated benefit of Charles’s reign, and long pageants were staged at each one. The following morning Samuel Pepys, the diarist and Secretary to the Navy Board, was up at 4a.m. to take his seat in a great scaffold across the north end of the abby – where with a great deal of patience I sat from past 4 till 11 before the King came in. And after all had placed themselfs – there was a sermon and the service. This time the sermon was a deal more sympathetic, drawing parallels between Charles and Christ as each sought to build a kingdom after a period in the wilderness.

Sample (above) of Pepys’s handwriting in 1700. He kept his Diary in code, and stopped writing it in 1669

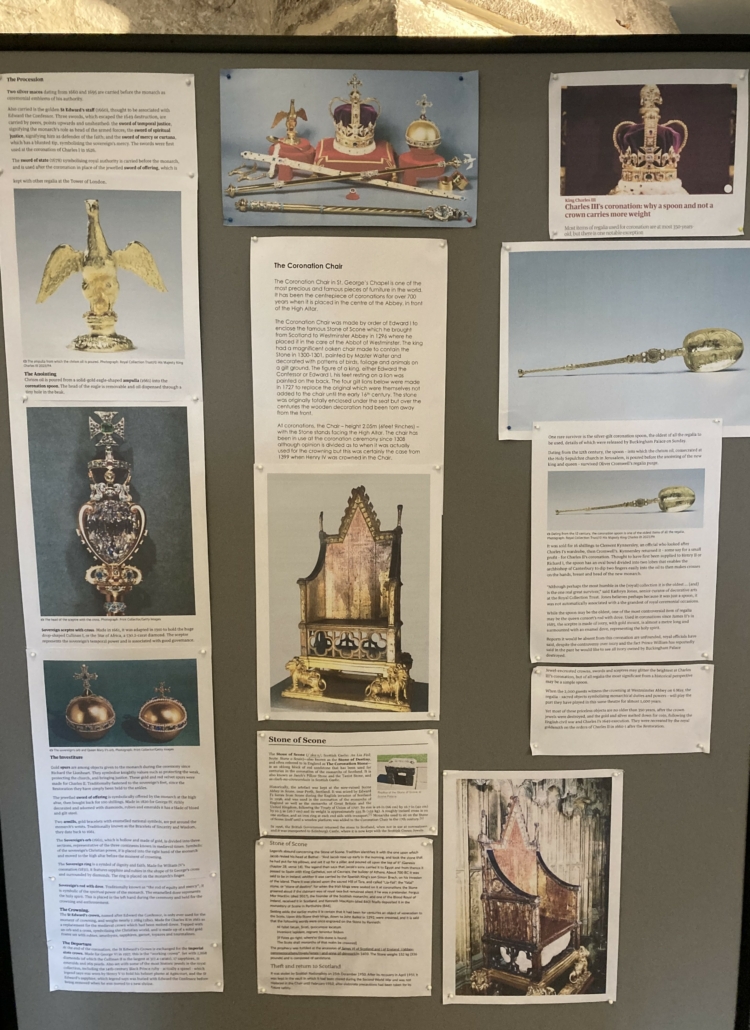

And then in the Quire at the high altar … all the ceremonies of the Coronacion – which to my very great grief, I and most in the Abbey could not see. These would have included investing the king with brand new coronation regalia, which had been purposely melted down during the Cromwellian era. The goldsmith, Sir Robert Vyner, re-created the royal crown of St Edward the Confessor (above), sceptre, orb and sword at a cost of £30,000. Pepys would also have been unable to see the anointing with holy oil, perhaps because the Barons of the Cinque Ports were holding a cloth of gold above the king. Both Charles and his subjects attached considerable importance to this part of the ceremony. In the next 25 years Charles exercised his assumed curative powers by touching 100,000 individuals for the ‘king’s evil’, or scrofula, a tubercular disease. There was an unseemly spat between the Barons and footmen of the royal household as they disputed ownership of souvenir pieces of the canopy. By this time Pepys was bursting and slipped outside to relieve himself. At Westminster Hall he saw the opening courses of the ceremonial banquet delivered to high table by nobles on horseback. His personal celebrations continued with copious drinking, and its consequences. Now after all this, I can say that besides the pleasure of the sight of these glorious things, I may now shut my eyes against any other objects, or for the future trouble myself to see things of state and shewe, as being sure never to see the like again in this world.

24 April. Waked in the morning with my head in a sad taking through the last night’s drink, which I am very sorry for.