Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was familiar with Shaftesbury, which he called Shaston in his Wessex novels, though he never lived in the town. He did live for two years at nearby Sturminster Newton, during which time he wrote The Return of the Native (published 1878). The fictional Tess Durbeyfield of Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) is born in the village of Marlott (Marnhull) – “several miles of pedestrian descent from that mountain-town [Shaston] into the vale.” The first sentence of the novel has John Durbeyfield, Tess’s father, back from market “walking homeward from Shaston to the village of Marlott, in the adjoining Vale of Blakemore or Blackmoor.” Though Shaston does not figure in Far From The Madding Crowd (1874), the 1967 film version sees Alan Bates as shepherd Gabriel Oak trudging up, while Terence Stamp (Sergeant Troy) leads a troop of yeomanry cavalry riding gingerly down, Gold Hill.

A number of thinly-disguised Shaftesbury locations feature in Jude the Obscure, Hardy’s last novel published in 1895. A circular walking tour of these places, starting from Gold Hill Museum, will take about an hour. “Shaston”, says Hardy, “was remarkable for three consolations to man. It was a place where the churchyard lay nearer to heaven than the church steeple, where beer was more plentiful than water, and where there were more wanton women than honest wives and maids.” The (abandoned) churchyard to which Hardy refers lies to the side of St John’s Hill at Bury Litton, an overgrown spot kept clear by local enthusiasts and marked by a few remaining gravestones. There is no trace of the medieval St John’s, and the church tower visible through the trees belongs to St James at the foot of the hill. Shaftesbury’s historic dependence on water carted from springs at the bottom of the hill is embodied in the Byzant mace preserved at Gold Hill Museum.

Hardy biographer Claire Tomalin writes that “Reading Jude is like being hit in the face over and over again.”

The two central characters, Sue Phillotson (nee Bridehead) and Jude Fawley, are both trapped in loveless marriages, and Jude, an unenthusiastic stone mason, has been denied academic opportunity at Christminster (Oxford). Jude follows Sue to her husband’s school in Shaston, the 1840s National School, now converted into private sheltered housing and known as King Edward’s Court. The stone name plaque from the school and the school bell, mentioned in Jude, are on display in Gold Hill Museum, Room 4 Life in the Town.

“The ringing of the school bell saved Phillotson from the necessity of replying …. they proceeded to the schools that morning as usual.”

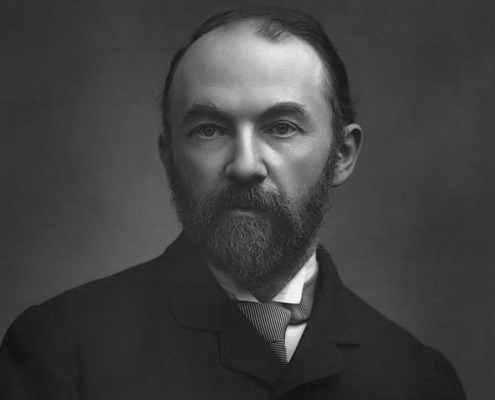

In 1932 the local High House Press published a Thomas Hardy-themed book of wood engravings, entitled Shaftesbury: The ‘Shaston’ of Thomas Hardy. This became one of their most sought-after titles.

Standing in the High Street, where its northern wall sinks right into the pavement, is the church of St Peter’s, an early fifteenth-century building in the Perpendicular style. The church has a noble tower …. this view from the South shows only the tower and the western porch. The house seen on the right was formerly the Sun and Moon Inn, the cellars of which ran under the church.

This cottage was bought in 1957 by The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society, and became part of what is now Gold Hill Museum. You can see the bricked-up entrance to the cellars in Room 2 Farming Life.

If you wish to follow the self-guided Thomas Hardy tour, please turn right on exiting the museum and make your way up to the High Street. To avoid the steps (which didn’t exist in 1932) you can walk across the top of Gold Hill and turn right past the entrance to the Salt Cellar.

If you walk up from Gold Hill to the High Street, turn left along Church Lane; Farnfields Solicitors is on the corner. As with Jude, your feet will take you “involuntarily … through the venerable graveyard of Trinity Church, with its avenues of limes.” At the far side of the churchyard to the right you will see the rear of Richard Phillotson’s school. Turn right along Abbey Walk, which is also mentioned by Hardy, and pass the front of the former National School. Please respect the privacy of the residents.

The former National School, now converted into privately-owned apartments and known as King Edward’s Court.

Kelly’s Directory for 1895 records that the average attendances were Infants 90; Boys 100: Girls 91.

Set up in 1811, the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales was largely the inspiration of Dr Andrew Bell. It used his Madras or Monitorial System of Pupil Teachers. From 1801 to 1809 Bell was rector of Swanage, where in 1806 he vaccinated over 200 of his parishioners against smallpox, perhaps influenced by the example of Dorset farmer and unsung vaccination pioneer Benjamin Jesty.

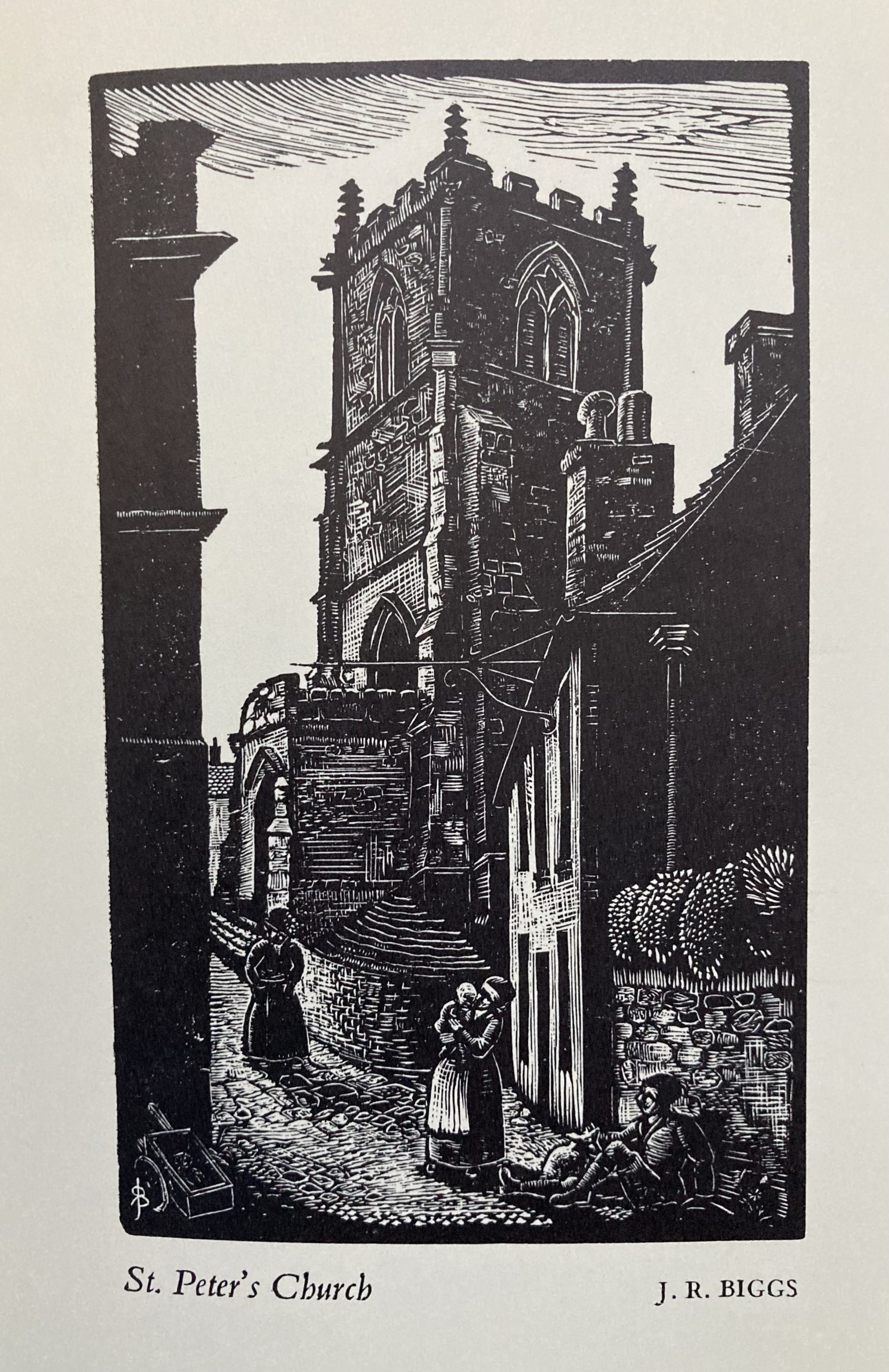

“She had said that she lived over the way at Old-Grove Place.” Cross Bimport to the left from Abbey Walk to see Ox House (Old-Grove Place) with its blue plaque marking the Hardy connection. Sue leaps from a bedroom window in a half-awake state. Fortunately: “Her fall, in fact, had not been a serious one, probably owing to the lowness of the old rooms and to the high level of the ground without.”

Please respect the privacy of the owners of Ox House. The interior is not open for inspection, but was recorded in John Biggs’s woodcut engraving of 1932 for the High House Press.

“Old-Grove Place …. whose walls were lined with wainscoting of panelled oak reaching from floor to ceiling.”

The text of the 1932 High House Press book on Thomas Hardy’s Shaston tells us:

Inside the porch is another and very massive iron-studded oak door which has a curious warped appearance. This quaint old door folds back in the centre, as may be seen in the wood-engraving, a view looking from the interior towards the entrance-porch.

Visible in the porch is a longcase clock. This might well have been made by a Shaftesbury clockmaker, as four or five were listed in the local trade directories for the first half of the nineteenth century.

At this point you can return to the High Street via two routes taken by Jude. While waiting to see Sue, Jude wanders along Abbey Walk to the “level terrace where the Abbey Gardens once had spread” (Park Walk). After their conversation inside the school – Mr Phillotson is absent at a teachers’ meeting in Shottsford (Blandford Forum) – Jude sets off along Bimport to catch the (horse drawn) coach to the station, probably Semley.

“Passing along Bimport Street he thought he heard the wheels of the coach departing, and, truly enough, when he reached the Duke’s Arms in the Market Place the coach had gone.” (The Grosvenor Arms).

The medieval New Inn, later the Red Lion, was a posting inn on the Great West Road. It was bought in 1820 with hundreds of other Shaftesbury properties by Earl Grosvenor and renamed the Grosvenor Arms.

Alternatively, you may continue along Bimport to where it turns sharply left and becomes St John’s Hill, to find on the right, the site of the abandoned churchyard, with its ancient yews. This is the “churchyard nearer to heaven than the church steeple.” Please take care as there are no pavements here. You can cross St John’s Hill to return to the centre of town via the wooded Pine Walk and Park Walk, where you will find Shaftesbury Abbey Museum and Gardens.

On 23 March 1539 Dr John Tregonwell received from the Abbess of the Benedictine nunnery at Shaftesbury the voluntary deed of surrender of the Abbey to the Crown. This ended the 650-year-old existence of Shaftesbury Abbey, founded by King Alfred. The Abbey Museum and Gardens on Park Walk are well worth a visit.

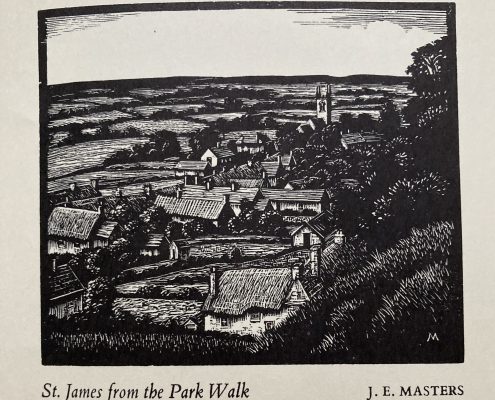

Hardy is eloquent about “Shaston’s magnificent apsidal Abbey, the chief glory of South Wessex, its twelve churches, its shrines, chantries, hospitals, its gabled freestone mansions – all now ruthlessly swept away.” There is some compensation in the stunning views from Park Walk and Castle Hill Green, on the far side of Bimport. The church visible from Park Walk and in James Masters’s engraving is St James, rebuilt by Wyatt 1866-67. Its tower is 65 feet high, but there is no steeple.

On a clear day it is said that from Castle Hill Green you can see Glastonbury Tor; on most days King Alfred’s Tower at Stourhead is prominent on the skyline.

Eventually, and with the resigned acquiescence of Richard Phillotson, Jude and Sue decide to run away together, though not to a life of happiness. The novel’s treatment of sex, marriage and the Church stirred up a hornet’s nest in late-Victorian Britain. The Bishop of Wakefield allegedly burned his copy, and booksellers sold it in discreet brown paper bags. It did sell well – 20,000 copies in England in the first three months. Hardy, however, published no new fiction, only poetry, until his death in 1928.