Tudor Accidents of the Month: May 2019

Tudor England was a dangerous place. There were plagues and wars, perilous childbirths and shocking infant mortality. But what risks did people face as they went about their everyday lives? Steven Gunn of Merton College and Tomasz Gromelski of Wolfson College are investigating this problem using evidence from coroners’ reports preserved in the National Archives. The four-year project entitled ‘Everyday Life and Fatal Hazard in Sixteenth-Century England’ is based in Oxford and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, with support from the Faculty of History and Merton and Wolfson colleges.

Professor Steven Gunn is the 2019 Teulon Porter Memorial Lecturer. At Shaftesbury Town Hall on Tuesday 24 September at 7.30p.m. he will give an illustrated talk on ‘Everyday Life and Accidental Death in Tudor Dorset and Wiltshire’. This event is free to members of The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society while non-members may pay £5 at the door.

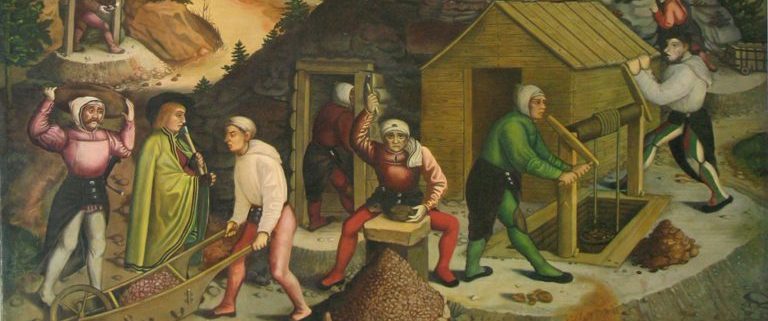

May 2019. Mining has always been dangerous. Although tin mining was one of Tudor England’s major extractive industries, accidents are not well recorded. This was because for much of the sixteenth century the coroners of Devon and Cornwall were less efficient in sending in their reports, and perhaps in holding their inquests, than those of other counties. Yet when fatalities do crop up they are eloquent. May 1571 brought the death of Ewen Taylor, struck in the stomach by an iron bar while mining at Ilsington, and Oliver Hannaford, wounded with his ‘tynhoke’ while digging for tin at Ashburton.

The depth of some tin works, reached by long ropes, caused the deaths of two other victims more indirectly. At Polgooth in St Mewan in Cornwall in February 1591, Thomas Hicke, tinner, was working at the tin mine when the ‘wynder wyndinge rope’ caused him to fall into ‘the Tynworke poole or pitt’, where he drowned. At St Neot in December 1588, Michael Tapnell hoped to exploit the depth of the mine to avoid arrest for debt when his creditor turned up from St Blazey to take him into custody, bringing two other men to help. He let himself down into the tin working on a rope, intending to slip away into the furthest part of the mine, but suddenly his hands slipped and he fell to the bottom of the pit and broke his neck.

Extracts from the website of the Everyday Life and Fatal Hazard in Sixteenth Century England Project by kind permission of Steven Gunn.