‘Young Elizabeth: Princess. Prisoner. Queen’ as told by the author

Dr Nicola Tallis is fast emerging as one of Britain’s most popular historians, according to fellow writer Gareth Russell. Her brilliant new study of the early life of Elizabeth I, says the doyenne of Tudor biographers Alison Weir, is an outstanding achievement. The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society is delighted to welcome Nicola to Shaftesbury Town Hall at 7.30p.m. on Tuesday 01 October as the 2024 Teulon Porter Memorial Lecturer. This illustrated talk is free to members and open to the public on payment of £5 at the door.

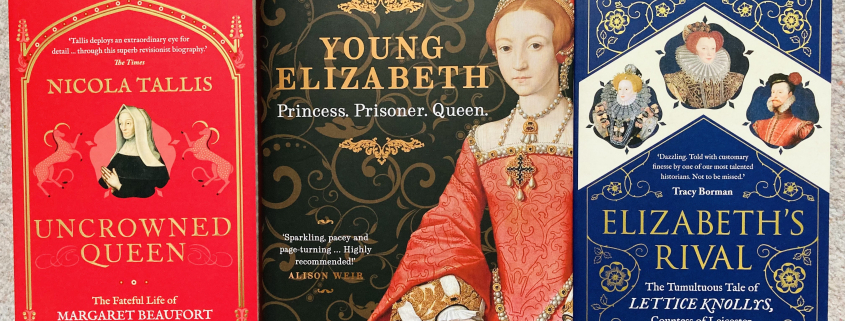

Nicola is a rising star in the firmament of Tudor historians. Her PhD thesis was published as ‘All the Queen’s Jewels 1445 -1548: Power, Majesty and Display’. She is speaking on this subject at a sold-out Six Lives Study Day at the National Portrait Gallery on 07 September. (Coincidentally Elizabeth I was born on 07 September in 1533.) After ‘Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey’ (2016), Nicola raised the profiles of other Tudor women in ‘Elizabeth’s Rival: The Tumultuous Tale of Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester’ (2017) and ‘Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort, Tudor Matriarch.’ (2019)

Elizabeth I was 25 when she became Queen in 1558. An awful lot of personal trauma was packed into her early years, starting with the execution of her mother, Anne Boleyn, on 19 May 1536. Elizabeth joined her elder half-sister, Mary (b.1516), in the non-status of officially decreed illegitimacy. Both were much reduced in rank and household, from Princess to mere Lady. Any sympathy Mary might have felt for her younger sibling tended to be crushed by her burning resentment at Henry VIII’s treatment of her mother, Katherine of Aragon, and harassment over her (Mary’s) traditional religious beliefs. Both were blamed squarely on the malign influence of Anne Boleyn. At the beginning of Mary’s reign, when Kentish gentleman Sir Thomas Wyatt raised an unsuccessful rebellion against Mary’s Spanish Marriage to the future King Philip II, Elizabeth found herself in the same Tower of London quarters, contemplating the same fate, as her mother.

Wyatt had planned to depose Mary and replace her with Elizabeth. If Wyatt had written to her, Elizabeth denied ever having received his letter. Her own ‘Tide Letter’ to Mary, the writing of which delayed Elizabeth’s passage to the Tower beneath the low arches of London Bridge (above), may have saved her from sudden retribution. Elizabeth also knew enough to score out the blank space at the bottom of her letter to prevent any forged additions.

This was not the first time that Elizabeth had to use her quick wits and inner resilience to rebuff bullying by male interrogators. In 1548 she had been part of the household of Henry VIII’s last Queen and widow, Katherine Parr. Katherine was now free to marry Thomas Seymour, uncle of the boy-king Edward VI, and in June 1548 they began residing at Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire.

In his will Henry VIII had made provision for advising his son Edward, aged 9 at his father’s death, to be shared by 16 executors. These were all male courtiers, though Mary was named second and Elizabeth third in the line of succession. Within days Edward Seymour subverted the terms of the will by being appointed Lord Protector, and Duke of Somerset. But Somerset’s nemesis was his younger brother, Thomas Seymour, who jealously coveted the post of Governor of the King’s Person. Although made Lord Admiral and given a barony as Lord Seymour of Sudeley, Seymour was not so easily bought off. Handsome, dashing and reckless, his consuming ambition made him a highly disruptive force. (John Guy, The Children of Henry VIII.) Thomas’s behaviour towards the 14 years-old Elizabeth was highly dubious, even by the lax standards of the day. He began to visit her bed-chamber at the crack of dawn. Lady-in-waiting Kat Ashley confessed that if Elizabeth were up, he would bid her good morrow and ask how she did, and strike her upon the back or on the buttocks familiarly … and if she were in her bed, he would open the curtains and bid her good morrow, and make as though he would come at her. Perhaps hoping to curb her husband’s excessive, abusive familiarity, Katherine took part in some of these romps, including a notorious incident in the garden at Hanworth where Elizabeth’s gown was cut to tatters as she was wearing it. I could not do withal, for the queen held me while the Lord Admiral cut it.

In May 1548, amid a rising tide of scurrilous gossip about the relationship between her errant husband and Elizabeth, Katherine sent the teenager to live with the Denny household. Within months, Katherine, who had been widowed three times, died of an infection sustained in childbirth. She was 36. Elizabeth learned from all these experiences. Thomas, thwarted in his schemes to groom Elizabeth, and to pitch a marriage to Mary, was arrested in January 1549 while trying to seize the person of the King. These were treasonous activities for which he was executed in March 1549. Sir Robert Tyrwhit, sent by Somerset to establish the extent of Elizabeth’s involvement, reported somewhat shamefacedly: I do assure your grace she hath a very good wit, and nothing is gotten of her, but by great policy. Legend has it that when in 1553 Elizabeth was released, reluctantly, by her sister from the Tower into house arrest at Woodstock, she used a diamond to etch into a window pane Much suspected of me. Nothing proved can be.