Shaftesbury can lay claim to being the cradle of the Dorset Button industry. As fashions, particularly for men, changed in the 17th century, from doublet and hose to waistcoat and breeches, the demand grew for button fastenings. Early buttons were hand-made using sheep’s horn and wool, readily available in North Dorset. Expertise in this domestic heritage craft was then passed down from generation to generation, providing families with home-based employment for over two centuries.

In 1622 Abraham Case moved to Shaftesbury and set up the first commercial button making enterprise. Originally from Gloucestershire, he had been a professional soldier in Europe during the Thirty Years War where he had observed French and Flemish button makers at work. On his return he married a local girl from Wardour before settling in Shaftesbury and setting up a workshop where his first buttons (Hightops) were a conical shape made from sheep’s horn, cloth and linen thread. These were favoured for men’s waistcoats and the bodices of women’s dresses.

As demand grew, buttons were made by outworkers who might combine labour on the land with piecework buttony. A skilled buttoner could make up to six dozen (72) buttons a day and earn up to three shillings (15p). This compared very favourably to wages of, perhaps, nine old pence (4p) a day for much more strenuous farm work. A flattened version of the Hightop was preferred for more flexible garments and called the Dorset Knob – possibly the biscuit of the same name resembled it in shape.

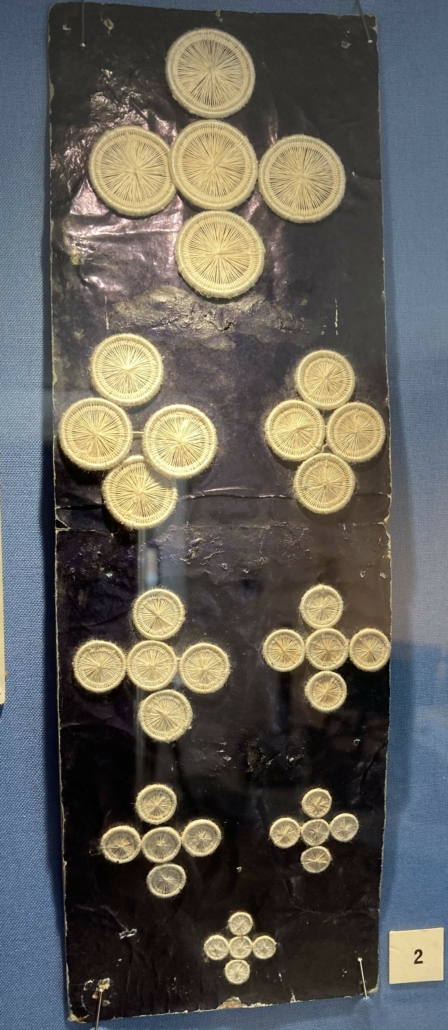

By the end of the 17th century, buttony had grown to be an important industry, still controlled by the Case family, while Shaftesbury was noted for its high proportion of pedlars and hawkers. Abraham’s sons Abraham jnr and Elias continued to manage the business, Elias opening a second depot at Bere Regis. By 1720 there were agencies at Milborne St. Andrew, Sherborne, Poole, Langton Matravers and Tarrant Keyneston. After a disastrous fire at Bere in 1731, a Yorkshireman, John Clayton, was engaged to reorganise the firm. Clayton had an interest in a Birmingham wire manufacturers, which sent wire by horse and cart to Dorset where children were employed as winders, dippers and stringers to produce metal rings by the gross (144). These replaced horn as the base for the many variations of the Singleton and Crosswheel designs. Where smaller and softer buttons were required, as for children’s clothes, the Bird’s Eye was stitched over a thread or fabric base.

Buttons were graded by quality. The finest export grade were mounted on pink cards, domestic quality on dark blue (right) and the lowest quality on yellow cards. Buttons retailed for between 8d (3p) and three shillings a dozen. A London sales office was set up in 1743, a major new depot at Lytchett Minster in 1744, and Abraham’s grandson Peter opened an export office in Liverpool. The business prospered until the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, with 4000 employed as outworkers.

Queen Victoria initiated a fashion trend with a white wedding dress (1840) decorated with Honiton Lace (examples can be seen in Room 5); she also owned a dress lavishly trimmed with Dorset Knobs. A square inch of Honiton (or East Devon) lace takes 8 to 10 hours to make. The decorative trimmings on the Queen’s dress were actually made by cottage workers in Beer over a six week period. As a promoter of innovation, her husband, Prince Albert, unwittingly contributed to the demise of widespread Dorset buttony. Inside the Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851, among the examples of the latest technology, was John Ashton’s button-making press. The mechanisation of button-making sounded the death knell of handcrafted Dorset Buttons. The factories of Birmingham became the centres of costume jewellery production. Many hundreds of rural Dorset families, impoverished by the collapse of buttony and agricultural depression in the late 19th century, became economic migrants to Australia, Canada and the USA.

In 2022 sculptor Bruce Williams installed a laser-cut steel artwork commissioned by the Lidl supermarket chain on the exterior of their new store in Shaftesbury. “Shaftesbury Lace Cattle” (right, in a photograph taken by Bruce from the Tesco car park) drew its inspiration from several sources, including the permanent exhibition in Room 5 at Gold Hill Museum, of Dorset Buttons and Honiton Lace. Bruce wished to commemorate the handicraft skills of past generations of Shastonians.

The life-size cattle reference the location of the store on the site of the former cattle market, closed in 2019.

They browse on a lacey horizon and are themselves composed of lace patterns and Dorset Buttons.

There is more detail about Bruce’s installation available by clicking here

Basil, Lavender, Poppy, Rocket, Rosemary, and Snowdrop are our Dorset Button Mice; they are hiding in six different display cases in various rooms, and waiting to be discovered by visitors of all ages.

Kits for making your own Dorset Buttons are on sale in the Museum Shop