An Expert View of the Dissolution of the Monasteries

On Tuesday 03 October at 7.30p.m. Professor James G. Clark of Exeter University will deliver the 2023 Teulon Porter Memorial Lecture at Shaftesbury Town Hall. In 2021 Professor Clark published a New History of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, to great acclaim. Reviewers typically described it as The best history yet written on English monasticism in the 16th century …. The fullest account of the Dissolution ever written …. This is a landmark book.

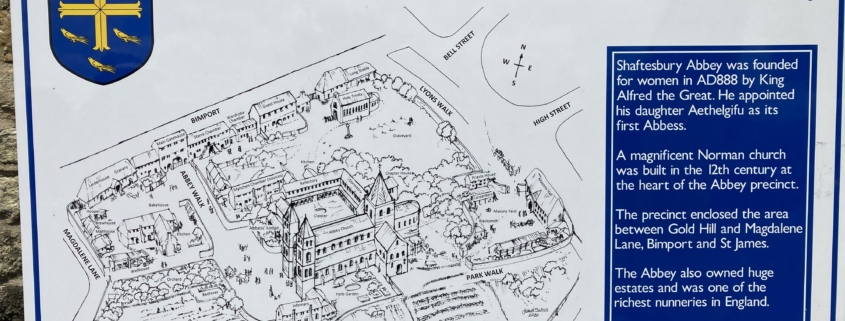

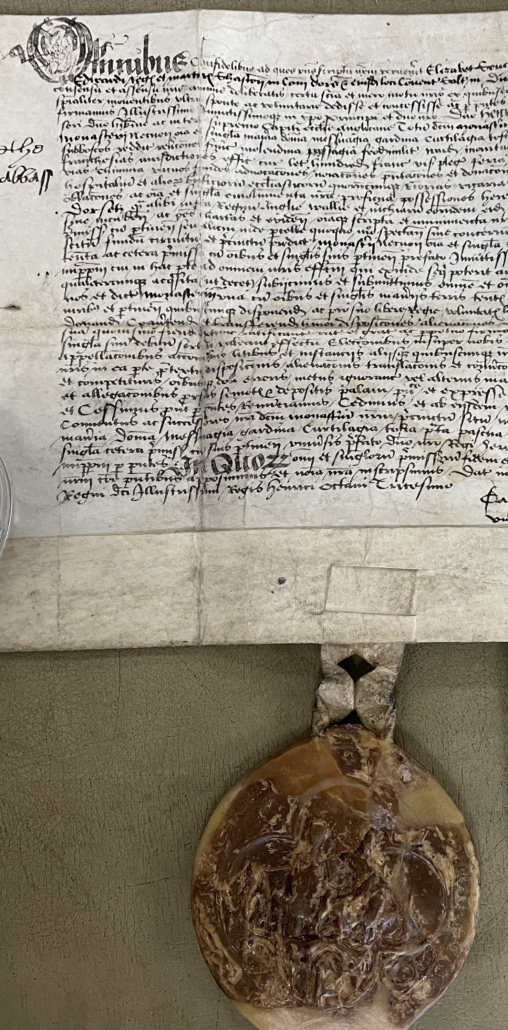

In Shaftesbury the final step in this religious, social and economic revolution took place on 23 March 1539, when Dr John Tregonwell received from the Abbess of the Benedictine nunnery at Shaftesbury the voluntary deed of surrender of the Abbey to the Crown. Thus ended the 650-year-old existence of Shaftesbury Abbey, founded by King Alfred.

Tregonwell was on the last lap of a ten-week sweep through the West Country during which he effectively closed down 21 monasteries. In the previous five days he had wound up the affairs of monasteries at Sherborne and Montacute, and next on his itinerary was the nunnery at Wilton. Each of the 57 nuns at Shaftesbury was allocated a pension, most between £6 and £3 6s 8d per year; the abbess, Elizabeth Zouche, received a monumental £133 6s 8d. The nuns, however, would have preferred to remain as a community, and in December 1538 had petitioned King Henry VIII and his chief minister Thomas Cromwell, to whom they offered 500 marks and £100 respectively, that they may remain here, by some other name and apparel, his Highnesse poor and true Bedeswomen. This plea, conveyed in a letter by Sir Thomas Arundell, receiver of rents for the nuns, and later purchaser of large tracts of Abbey lands, fell on deaf ears.

When Henry VIII’s commissioners had first visited Shaftesbury Abbey in 1535, scarcely a hint of scandal, lax behaviour or superfluity to requirements was detected. A minor revelation was the disclosure of the true identity of young nun Dorothy Clausey, who was the illegitimate daughter of Cardinal Wolsey. Under regulations drafted by Cromwell, the 24-year-old Dorothy could have left the nunnery on the grounds of her youth, but she chose to remain and appears in the 1539 list of pensioners at £4 13s. 4d. The 1536 Act of Suppression applied to smaller monasteries, with incomes of less than £200 per year, and often unviable in terms of numbers of clergy. This recycling of religious resources and personnel was neither unprecedented nor particularly unusual. The prioress and two nuns from Cannington in Somerset duly transferred to Shaftesbury. The Abbey, with annual revenues of £1166, belonged rather to the category of great and solemn monasteries of this realm wherein, thanks be to God, religion is right well kept and observed.

So why was there such a dramatic change in royal policy towards the monasteries? And why was there, in the West Country, no significant resistance to the process of closure? (Unlike the violent Pilgrimage of Grace in the North).

The scholar best qualified to answer these and other questions about the Dissolution is undoubtedly Professor Clark. The title of his talk is The Dissolution of the Monasteries: Shaftesbury and the South-West. It is free to members of The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society and open to interested members of the public on payment of £5 at the door. Seats may be reserved by emailing enquiries@goldhillmuseum.org.uk