Two Hundred Years Since A Second Outbreak of Fonthill Fever

On 09 September 1823 the sale by public auction began at Fonthill Abbey of most of the contents of reclusive slaveowner William Beckford’s fantastical Gothic creation. The initial sale of Beckford’s estate, including the house and its artistic treasures, had been advertised for 17 September 1822. Captivated by Beckford’s acknowledged reputation as a wealthy connoisseur and by the impenetrable secrecy of his pleasure dome, the public found itself afflicted by the ‘Fonthill Fever’, as Thomas Dibdin characterised it. (Robert J. Gemmett writing in the Beckford Society’s Exhibition Guide, available in our shop). But this first sale was twice postponed, and then abruptly cancelled, as Beckford struck a secret deal with a private purchaser. Naturally, there was considerable disappointment, not to say anger, at this turn of events. Humbug Fonthill Abbey said one headline.

The new owner, John Farquhar, had made a fortune supplying gunpowder to the British government in India, and was a major shareholder in Whitbread’s brewery. The ink was not long dry on the final sale agreement in March 1823 when Farquhar decided to sell the contents of the house he had just bought. Constant assurances were made in the press that the sale would take place as advertised – and so it did, but not without provoking its own controversial headlines

Thomas Dibdin, coiner of the ‘Fonthill Fever’ phrase, wrote to the Morning Chronicle before the start of the auction to complain that many of the rare books he had seen in 1822 were now missing. Possibly Beckford had taken them with him to Bath; he always regretted leaving most of his library, and sent an agent who bought over 640 lots in the book sale. Other allegations were laid that many of the books were ringers that had never been in Beckford’s library, and that hundreds of paintings in the 1823 catalogue had never been owned by Beckford. Thomas Adams Jr., a bookseller from Shaftesbury, said that he never was at a Sale where so much suspicion and jealousy reigns.

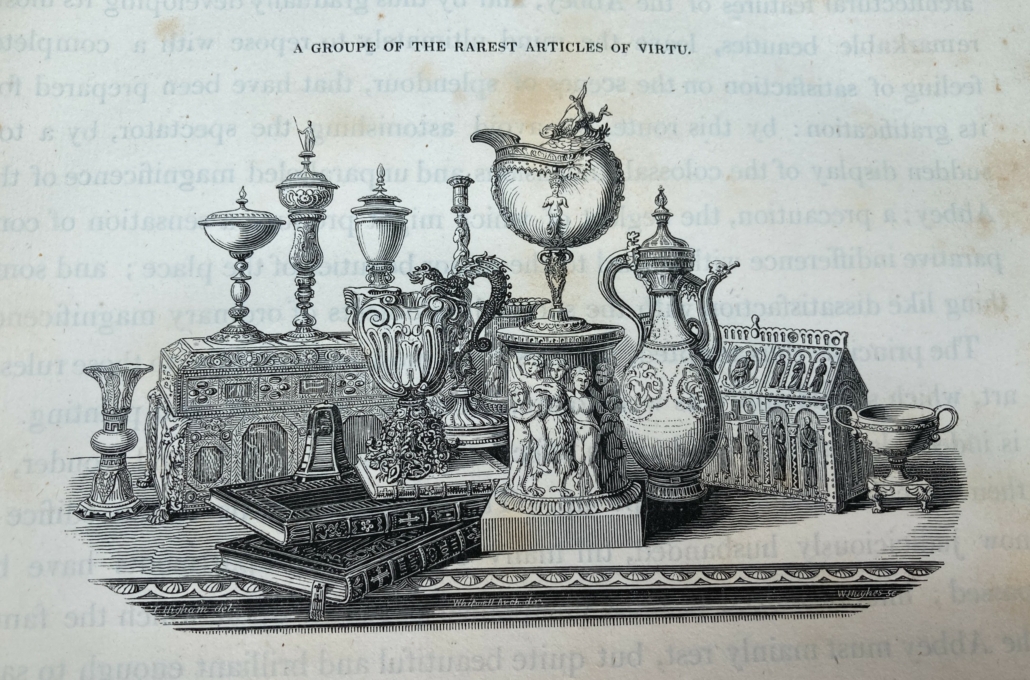

Lot 1567, offered for bidding on the 32nd day, stirred up a furore that made more headlines in the press and was even spoofed in a Christmas pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The ‘Cellini topaz vase’ (above left) was, according to silversmith and antiquities dealer Kensington Lewis, neither made of topaz nor by Cellini. Subsequent expert analysis confirmed Lewis’s opinion that it was rock crystal, and had no credible provenance to link it with Cellini. Beckford had bought it in 1819 simply because he liked it, and chose to overlook its dubious pedigree.

The sale concluded on 29 October 1823. Magnificent works of art and items of furniture had been snapped up by private collectors, which now grace some of the world’s great museums. Farquhar had been a generous host, and on the evening of 22 October he organised a late-Georgian version of a ‘son et lumiere’ spectacular. Robert J. Gemmett writes:

All of the heavy curtains were pulled aside in the Abbey to expose candlelight flickering its incandescent glow in every room. Light poured out through the windows radiating the colours of the stained-glass portraits and the array of rich heraldic symbols. The lantern in the tower streamed its radiance against the dark sky to the silent amazement of those stationed on the lawn. The doors of the Abbey were then thrown open to the onlookers … to enhance the visual effects, the grand organ filled the air with its ‘high and holy harmony’ … It was a fitting farewell for this palace of enchantment …

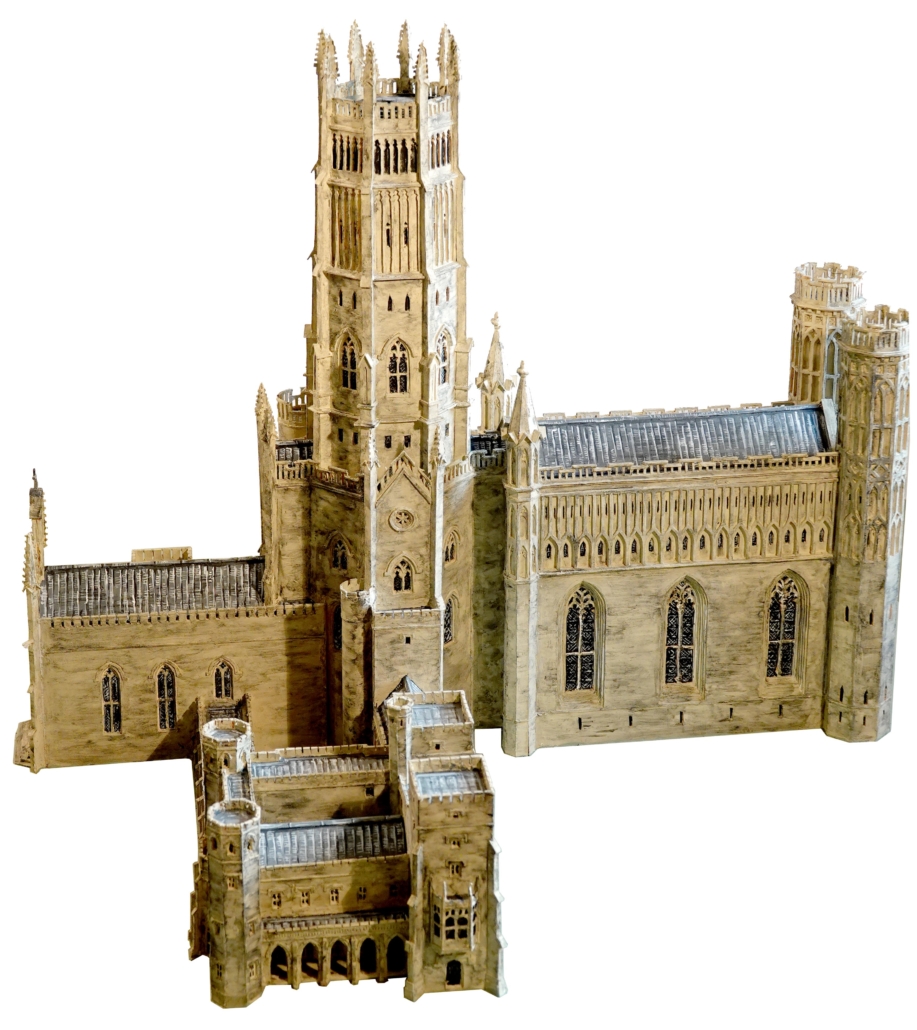

William Beckford had begun to hate his ‘palace of enchantment’, writing in a letter of December 1818 … in cold weather the Octagon is a horror, an inferno of draughts, and has an atmosphere of ice …this place makes your flesh creep as soon as night falls … the horrible din of the winds last night. I didn’t sleep a half-hour in succession … Really this habitation is deathly in the stormy season … At 3.30p.m. on 21 December 1825 the central tower collapsed, reducing much of the structure including King Edward’s Gallery (at the head of this blog) to rubble. Farquhar and his servants escaped unharmed, though one man was catapulted along a corridor by a blast of air.

The Fonthill Fever temporary exhibition is free and runs until the end of our season on Tuesday 31 October. Dr Amy Frost, the Curator of Beckford’s Tower and Museum in Bath, returns on Tuesday 09 January 2024 to update the S&DHS on all things Beckfordian. Lectures & Speakers – Gold Hill Museum