From Private Banker to Aesthetic All-Rounder and Shaper of Stourhead

At 2.30p.m. on 09 April at Gold Hill Museum, the National Trust’s Collections and House Officer at Stourhead, Hannah Severn, will give an illustrated talk on The Life and Work of Sir Richard Colt Hoare (1758-1838): Artist, Antiquarian, and Traveller. While it was the two Henry Hoares, Richard’s great-grandfather and grandfather, who first built the Palladian mansion and then created its magnificent landscape garden, he made significant additions and alterations to both, as well as proving to be an accomplished artist, archaeological pioneer and author of compendious Histories of Wiltshire. In pursuing these interests his life intersected with those of William Beckford and John Rutter, key figures in the history of Shaftesbury and District. The talk is free to members of The S&DHS, and seats should be available from 2.20p.m. for non-members on payment of £3 at the door.

The money to finance the purchase of the Stourton estate in 1717 came from the profits of Hoare’s Bank, founded in 1672 – early customers were Samuel Pepys and Queen Catherine of Braganza. Not all private banks flourished; many went under at the time of the foundation of the Bank of England in 1694, and in the wake of the share-buying frenzy of the South Sea Bubble in 1720. (The South Sea Company had been granted a monopoly of the supply of African slaves to the islands in the “South Seas” and South America.) Henry Hoare II was determined to separate the finances of the Bank from those of the Stourhead estate, so that the latter would remain in the family if ever the Bank failed (it is still in business). Therefore Richard Colt Hoare inherited Stourhead in 1783, on condition that he severed all connections with the Bank, where he had been working. In the same year he married the lively Hester Lyttelton.

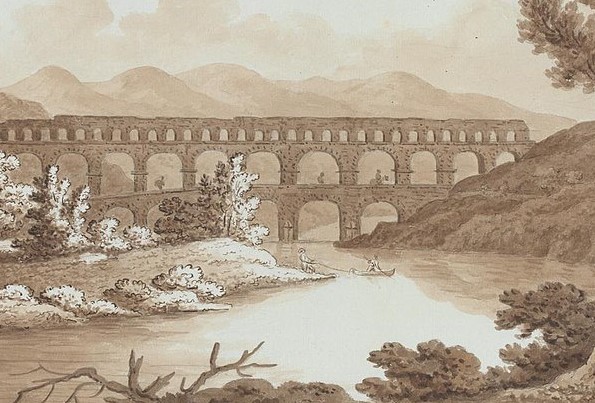

In 1785 Richard’s world, already subject to family tensions over his inheritance, fell apart when Hester died after giving birth to their second child, who did not survive. Within weeks Richard left for an extended Grand Tour of Italy, France and Switzerland, which lasted until 1791. From having been one of the most settled men in the world I am become the most fickle. I hardly know where I shall sleep the next night. (Later) there is so much work for my pencil that I know not when I shall be able to get away.

Richard filled the shelves of his new Library with bound volumes of sketches and commentaries, plus topographical works on the countries he had visited. He now undertook similar tours of Britain and Ireland. His 1802 exploration followed the interesting and highly curious itinerary of Giraldus Cambrensis through north and south Wales in the year 1188 [with] drawings to illustrate it. Gerald of Wales was an ambitious Norman / Welsh monk who accompanied Baldwin, Archbishop of Canterbury, on a seven-week, 600-mile recruiting campaign for the Third Crusade. Colt Hoare’s translation from the Latin, published in 1806, brought Gerald’s quirky description of Welsh manners and wildlife to a wider audience, and is still an entertaining read. The furnishings of the new Library and Picture Gallery, including the ornate carved frames of massive Old Master paintings, were the work of Thomas Chippendale the Younger.

In January 1797 one of the three standing trilithons at Stonehenge collapsed. William Cunnington was one of the antiquarians attracted to the scene, and began investigating what had been beneath the stones. He probably met Colt Hoare through a mutual friend, William Coxe, Rector of Stourton, and all three were interested in trying to understand the ancient landscape of Wiltshire. Colt Hoare became patron of a team in which Cunnington, Stephen Parker and son John, all from Heytesbury, did most of the digging, and Philip Crocker produced impeccable maps and artwork of their finds. According to Julian Richards Between 1803 and 1810 Cunnington and his team opened 465 barrows in Wiltshire, nearly 200 of them in the area around Stonehenge. (Stonehenge; The story so far Historic England, 2017, p78) Modern archaeologists probably wish that they had not done so, but this was more than mere treasure-hunting, and Colt Hoare published his findings in his multi-part Ancient History of Wiltshire 1810-21. It is still, along with Cunnington’s original notes and correspondence, a valuable resource for today’s students of prehistory. (Richards, p85).

There were even more instalments of The History of Modern Wiltshire, to which he contributed from 1822. Some of this was published by Shaftesbury printer John Rutter, whose Delineations of Fonthill, to which Colt Hoare was an early subscriber, appeared in the wake of Beckford’s sale of Fonthill Abbey in 1822. Colt Hoare had long been interested in what the reclusive Beckford was building and furnishing behind his high stone walls, but was warned off associating with the social pariah. Joseph Farington wrote in his diary for October 1806 that Sir Richard Hoare of Stourhead applied to Mr. Beckford to see the Abbey … the neighbouring gentlemen took such umbrage at it … that a gentleman wrote to Sir Richard in his own name and that of others to demand of him an explanation.