Dave Hardiman on “The Cantankerous Clergyman” of 1870s Shaftesbury

“If he were not a clergyman, I would give him a good thrashing.” The full text of the story first told on the Alfred Daily podcast.

During the 1870’s, the peace of Shaftesbury was much disturbed by a man who was variously described as the ‘Quarrelsome Vicar’, ‘The Political Parson’, ‘Persecuted Preacher’ and the ‘Cantankerous Clergyman’. There is much more that I could relate to you about this man and what became known as the ‘Shaftesbury Outrages’, but I am limited by time here.

The Cantankerous Clergyman.

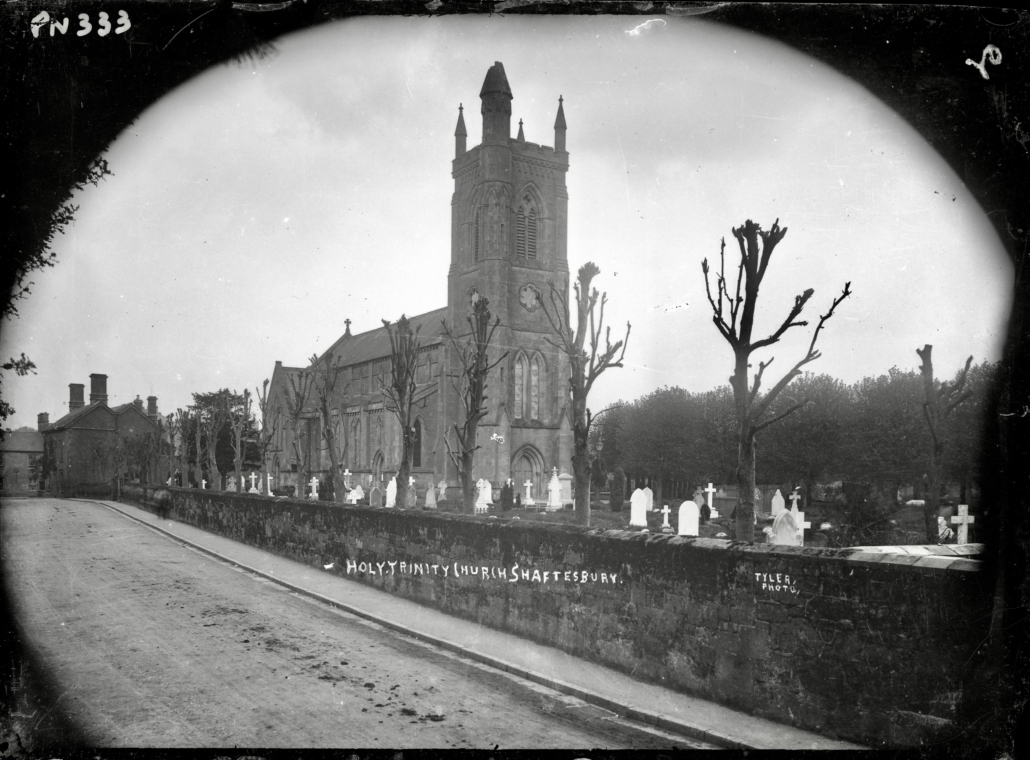

In October, 1870, there came to Shaftesbury, a Rector who would spend the next 9 years or so, causing a tremendous amount of hostility and dissension among the people of the town. His name was Thomas Knox Magee Morrow, an Irishman aged about 51, who was installed as Rector of the parishes of Holy Trinity and St.Peter’s. He lived with his wife, Elizabeth, and a couple of servant maids in the Rectory.

In July, 1871, some malicious person or persons broke several panes of glass at the Rectory while he was away. But, apart from this seemingly isolated incident, all appears to have gone relatively smoothly during the early months, with the Rector fulfilling his duties as would be expected.

Although he was gaining a reputation as a rather eccentric clergyman, it is not until 1873, that his actions and rhetoric from the pulpit, began to create enemies and a groundswell of ill-feeling against him.

Some 50 years earlier, John Rutter, had published a document entitled ‘A brief sketch of the state of the poor in Shaftesbury’, which was a shocking and revealing account of the appalling conditions in which some of Shaftesbury’s residents lived. At that time, most of Shaftesbury was owned by the Grosvenor family and many Shastonians were their tenants.

However, it seems that housing conditions had been much improved by the Grosvenors during the intervening years and Lady Grosvenor in particular, was very much respected by the people of Shaftesbury. In addition, her family were in the process of building the Westminster Memorial Hospital, which was to open in 1874.

However, setting himself up as a champion of the Agricultural Labourer, the Reverend Morrow elected to publish a pamphlet which contained the following:- ‘Notwithstanding the beauty of the landscape, and the plenty that is around you, to many of you the lines have fallen in anything but pleasant places. It is the lot of not a few to be poor, and besides being thrown upon parish relief, they are obliged to reside in miserable dwellings, wholly unfit for human habitation’.

Lady Grosvenor’s local agent was a man named George Genge, who was a 54 year-old farmer living in the parish of St.James. Genge was infuriated that Lady Grosvenor could be criticised in such a way. It seems that Mr Genge made his feelings known to all who wanted to listen and soon incited a group, who would become known as the Shaftesbury ‘Ruffians’, to take action against Morrow.

As her Ladyship’s agent, Genge felt entitled to challenge Morrow and, on the 18th, January, 1873, that is exactly what he did. He saw Morrow in town and confronted him in the Post Office, where an abusive exchange took place ending with Morrow grabbing Genge by the collar and attempting to throw him out.

Genge challenged Morrow to name the houses referred to in his pamphlet, but Morrow refused. Genge called Morrow a ‘Disgrace to the Ministry, a slanderer and a liar’. He also told him that he never ought to have been a clergyman. He went on to tell Morrow that he had been a cause of dissension ever since he came to Shaftesbury and that he had made use of his pulpit to vent his abuse. Since he had arrived, he had quarrelled with everybody and had no real friends in the town. This exchange led to a court appearance with both men counter claiming for assault.

Next, in August, 1873, Morrow was summoned to court for assaulting his Churchwarden, Mr Buckland. Buckland said that while he was posting a notice on the Church doors, the Rector came up behind him and grabbed him by the neck with his right hand and tore the notice down with the other. He said that he had to grab the Rector’s coat to save himself.

Moving on to January, 1874, Morrow was summoned before the court again, charged with assault. The Judge noted that this was now the 4th or 5th time that the Reverend had appeared before him on such a charge.

During 1874, elections took place and, in February, during the lead up to the election, the sitting M.P. for Shaftesbury, Mr Bennett-Stamford (Conservative), in an address to the electorate at Shaftesbury’s Commons, said that ‘The Reverend Morrow, having taken it upon himself to slander my good name ……he hoped few others possessed the same quarrelsome temperament.’

In March, 1874, Morrow took Mr Francis Webb, bank clerk, and George Genge to court, accusing them of using threatening language towards him. Challenged by Genge, Morrow admitted that he had been previously fined 1/- for pushing a boy, but caused laughter in the court when he also said that he did not touch the boy. Morrow also admitted that he was bound over for an assault on Mr G. Hatchard. Genge went on to accuse Morrow of abusing him from his pulpit, Morrow saying that there was ‘An iniquitous man in power in Shaftesbury,(meaning Genge), who treated people with drink’. Morrow denied saying this. Morrow accused Webb of verbally abusing him in Mr Freke’s shop, Webb saying that, ‘If he were not a clergyman, I would give him a good thrashing’. Morrow said that Webb followed him and he had to seek refuge in the Police station.

In March, 1875, there was a Coroner’s inquest into the death of a one month old child named Arthur Pitt at the Sun & Moon Tavern on Gold Hill. When the child was a week old, the Mother, Louisa, had asked Morrow to come to her house to baptise him. Morrow told her that he would open the Church at any time, but refused to go to her home.

The Mother stated that the child had been small and delicate and did not grow after birth and her Doctor had expressed doubt that the child would survive and she, noticing that the child was weakening and being afraid that he would die, took him to St.Peter’s to have him baptised. She had sent her sister to request Morrow, but he now refused to come because her husband was not a Churchman. That night, the child died in bed at his Mother’s side.

In December, 1876, the Rectory windows were broken again. Following this, Morrow decided to get posters printed and have them put up around the town. The posters offered a reward and read as follows:-

‘Outrage and Reward. Whereas, about 10 o’clock on the night of the 6th, November past, a number of evil-disposed persons assembled in front of my Rectory House, broke several of the windows, battered the hall door with iron missiles, and tried to burn the house by means of tarred cloth set on fire and inserted among the shrubs which grow on the walls of the house; and whereas about a quarter to two on the morning of Sunday, 17th, December, some evil-disposed persons threw large stones through the window of one bedroom and broke the glass of a window in another room of the Rectory, and then demolished the woodwork as well as the glass of the dining room window; and whereas the local authorities appear afraid or unwilling to deal with the promoters of the outrages, I hereby offer a reward of £10 (£1,000) to any person or persons who will furnish me with such information as will lead to the conviction of the projectors and perpetrators of these outrages’.

This caused some more controversy as he was refused permission to put them up. He did however, have the text published in the Western Gazette, which prompted some to write to the Western Gazette about the Rector.

In January, 1877, a ‘Ruffian’ wrote:-

How is it Mr Morrow is so at odds with everyone in the town, and how is it that rich & poor, gentle & simple, clergy, lawyers, doctors, tradesmen, mechanics, servant girls, labourers, horse dealers and drovers; I say how is it that all these are of one opinion respecting this persecuted gentleman? The answer is contained in a pamphlet dated 08/02/1873, ‘If one should happen to be unfortunate enough to dissent from Mr Morrow’s views upon even the most trivial subject, straightaway the opportunity is seized to indulge in intemperate and unguarded language, and far worse, scurrility-railing accusations, having no foundation whatever, save the distempered imagination of this clerical gladiator’.

Another Ruffian stated that Morrow from his pulpit will not name names, but will ensure that the congregation knows who he refers to. Speaking about one individual, he accused him as ‘Totally unfit to have the care or instruction of youth, for he is an associate of Mountebanks (fraudsters) and frequenters of dram shops and cricket fields’. Alluding to poor attendance at his church; ‘Where are those that should be worshipping in the same place as their forefathers have in years past?’ They are skulking under the hill, listening to the mild platitudes of a neighbouring clergyman’. During sermons, bringing his fist down onto the Bible, he roars out, ‘Listen to this ye cowards of Shaftesbury!’ The writer went on to say that, about a month ago, I was skulking under the hill, going to evening service at St.James and came upon two boys of about 15 or 16 who, on meeting one another, said “Hullo Bill, bist gwine to Church?” “I dunno”. “Come on. Twill be a lark: Old Morrow’s bound to pitch into somebody”.

Another letter from someone who called himself a ‘Skulker’, professed not to be of the anti-Morrow clique, but went on to comment on Morrow’s assumed right to speak on behalf of his parishioners and how he showed either a reckless disregard of the known facts, or a total ignorance of public opinion. He went on to say that:-

‘From personal observation, I assert fearlessly that every class has been disgusted by the violent conduct and language of the Rector of Shaftesbury, more especially as his attacks emanate from the protection of the pulpit’. The writer stated how the efforts of the town to establish an amateur dramatic Society, had been described by Morrow as ‘Soul-destroying indulgence’, a Device of Satan’ and ‘Den of Belial’.

Finally, in March, 1879, Morrow resigned and was replaced by the Reverend Flyn.

But it wasn’t quite all over and, in April, 1879, following his resignation, Morrow was sued by George Gatehouse, Clerk & Sexton at Holy Trinity, for £13-7s-6d, (£1,500), which represented his expenses for washing, cleaning, attending to the Bishop’s visitation and opening the Church on Sundays. Until Easter 1873, all such expenses had been met from what was known as a voluntary pew assessment. Morrow abolished the pew assessment and introduced an offertory. Gatehouse said that he did not know what Morrow did with the money from the offertory but, whatever he did, he did not pay him, nor had he been paid since. Morrow had appointed George Gatehouse as clerk, but when he presented Morrow with an account, the Rector threw it back at him, saying that it was nothing to do with him and that the Churchwardens should pay him. The problem was that as Morrow kept the offertory money, the Churchwardens had no money with which to pay. Needless to say, George Gatehouse was awarded compensation.

Morrow was gone, the old pew assessment system was re-instated and congregations returned to the two Churches. At last, peace reigned again in Shaftesbury.