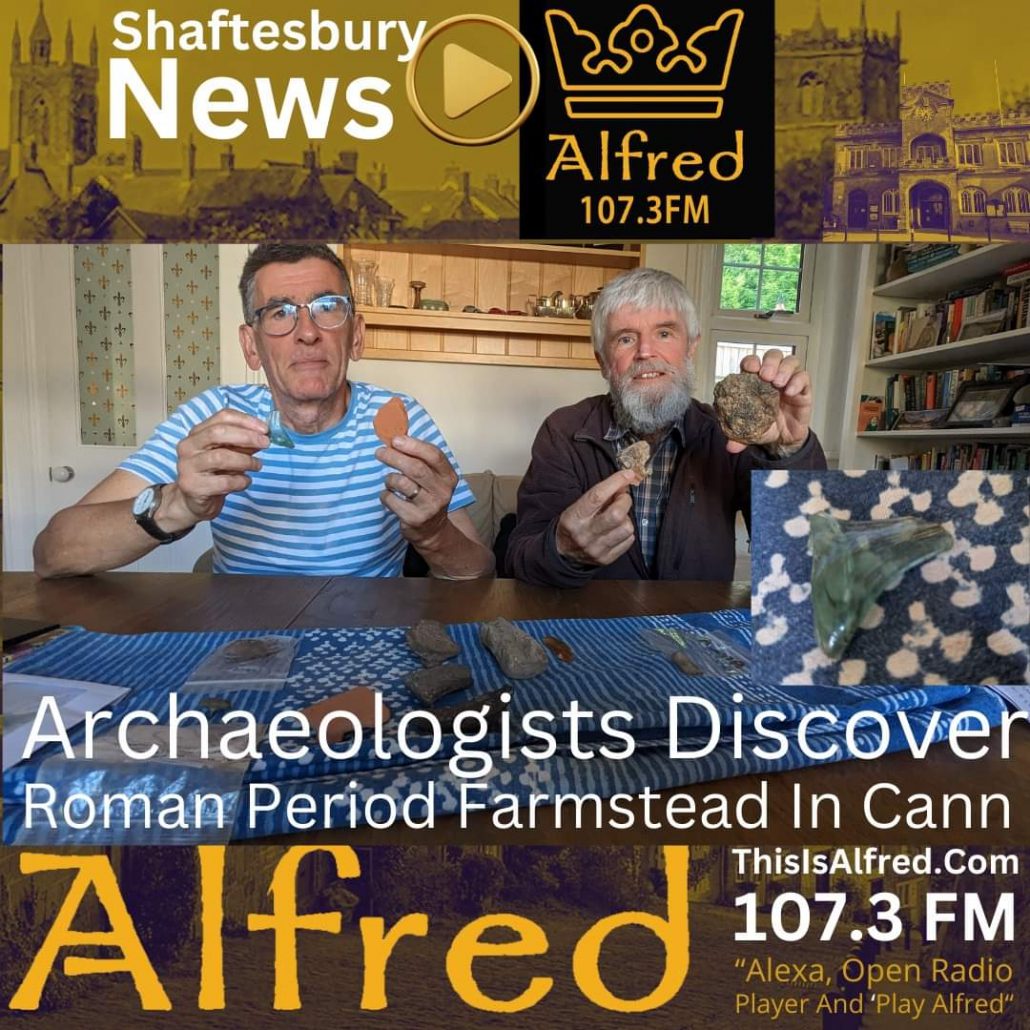

See ‘The Goddess, the Hound and the Fox’ for free

From Tuesday 01 April free-to-enter Gold Hill Museum is open every day. Its volunteer supporters have been hard at work during the close season preparing two new temporary exhibitions and much larger shop, office and storage spaces. The intriguingly titled The Goddess, the Hound and the Fox presents the exciting discovery of a previously unknown Romano-British settlement near Shaftesbury by two Historical Society members and keen amateur archaeologists, Matthew Tagney and Peter Stanier. Much of the evidence was simply picked up from the ground, having been brought to the surface by ploughing and the action of the weather. (See the headline image. You do, of course, need to know what you’re looking for, and have the landowner’s permission.)

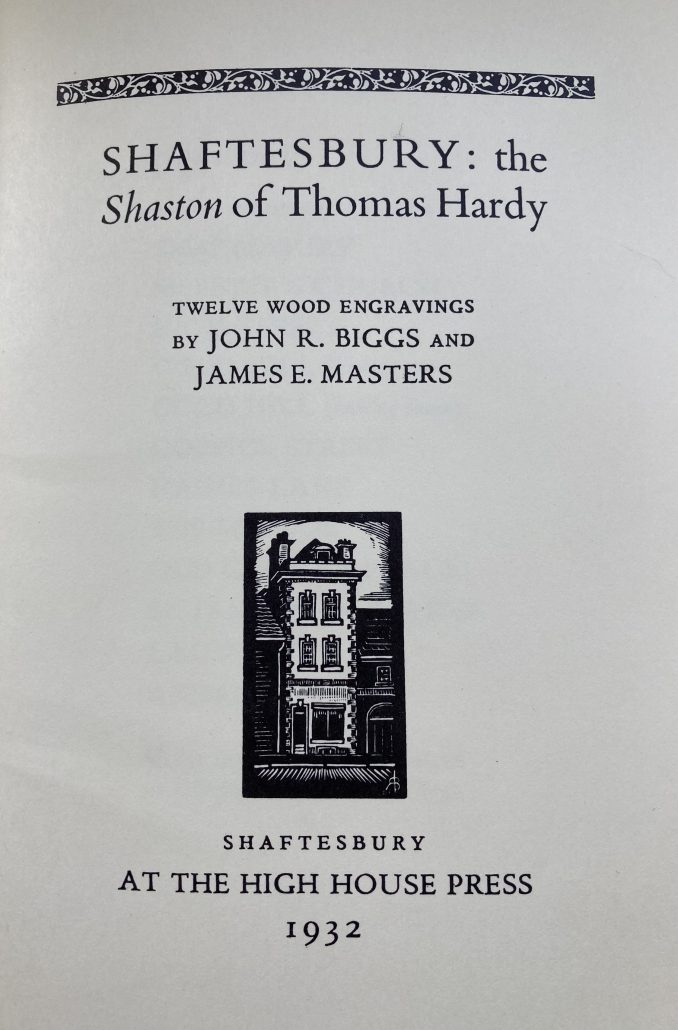

There was a brief window of opportunity in February to see our other new temporary exhibition The High House Press. We are grateful to Matthew and Peter for providing the images in this blog, and all the words that follow about their exhibition:

This temporary exhibition at Gold Hill Museum from April to October 2025 tells the story of discovering and investigating a previously unrecorded Romano-British farmstead in the parish of Melbury Abbas and Cann near Shaftesbury. It shows just how much can be achieved by amateurs “in the field”; and along the way, we meet a goddess, a hound, and a fox!

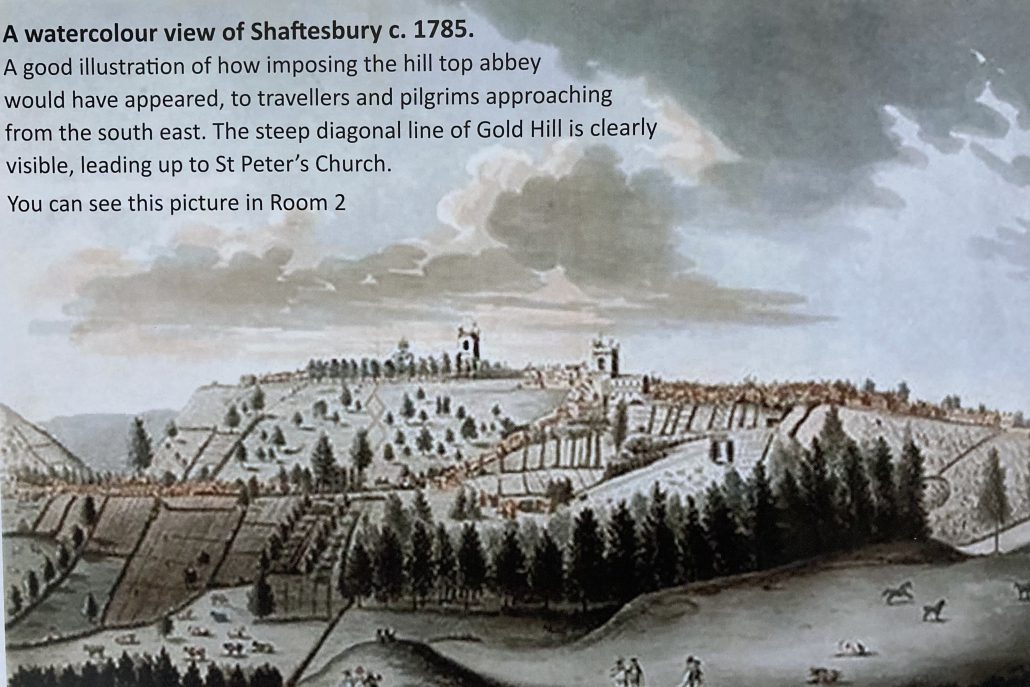

The exhibition, focused on the Roman site’s discovery, also tells two intertwined stories: first, of settlement here across time; and second, of the Roman period in this area. The wider area has a long history of human occupation from at least Mesolithic times, over 6,000 years ago. The site has open views towards surrounding hilltops with ancient activity: Melbury Hill, Fontmell Down, Hod Hill, Hambledon Hill, Rawlesbury, Nettlecombe Tout, Dungeon Hill, Stourhead Woods, Whitesheet Hill, and of course Shaftesbury. Known Romano-British sites are at Ashmore (Roman Road east of village), Iwerne Minster, Hod Hill, Shillingstone, Todber, Duncliffe Hill, Gillingham, Mere and Shaftesbury.

Until very recently there was no indication of any Roman or prehistoric site at this location, despite many finds recorded in surrounding areas. But in 2023, regular ploughing of a field crossed by a public footpath turned up first a stone-age flint tool, then fragments of Roman-era pottery. These first finds, once confirmed by experts, led to further investigations organised by Shaftesbury residents and archaeology enthusiasts Matthew Tagney and Peter Stanier, with local volunteers, specialist advice and professional support; and with thanks to the landowner for permission.

The finds discovered in 2023 and 2024 came mainly from “surface collection”, or field-walking, supplemented by a small excavation.

After initial discoveries were confirmed as prehistoric and Roman, permission was obtained for field-walking: systematically spotting items brought to the surface by ploughing and rain. Roman expert Mark Corney (from Channel 4’s “Time Team”) was invited to review the results. Many fragments had abrasion from acid soil and ploughing, but Mark identified pottery from early to late Roman, all from one limited area: it suggested a previously unrecorded settlement.

The next phases of investigation were:

• metal-detecting – which turned up a Roman coin with the image of a goddess;

• geophysical survey – which revealed possible features; and

• limited excavation: guided by geophysical results in choosing where to dig, with volunteers who had previously worked together on a Shaftesbury Abbey dig featured on BBC TV’s “Digging for Britain”.

Nearly 10 kilos of Roman potsherds was found, including Dorset-produced vessels similar to Roman-era styles found in an earlier landmark excavation at Greyhound Yard, Dorchester. As well as pottery from over 300 years of everyday cooking and dining on the farm, finds included higher-status items (one fragment decorated with the image of a hound’s hindquarters, tail up and legs stretched); evidence of iron-working in a blacksmith’s hearth; and a range of prehistoric worked flint.

But of course digging is not the end: after that comes cleaning every find, marking them with a site code; and then specialist reports, e.g. by Dr Richard Massey of Ridgeway Heritage on the pottery assemblage. Dr Denise Allen advised on a Roman glass fragment; Julian Richards (who led the Abbey dig) picked out the best prehistoric flint tools for including in this exhibition. The display also shows what emerged from the field from later centuries, including thimbles, a Cavalry button, horseshoes, and a fragment of glass from the world’s largest bottle factory!

Conclusions to date are that this project has confirmed a previously unsuspected farmstead on this site, persisting throughout Rome’s occupation of Britain (1st to 4th Centuries AD). This is important: the Roman period in this part of North Dorset is still poorly understood, and we’ve added a new point on the map. Also, this site had been a place of settlement for thousands of years before; and finally, it revealed traces of human occupation from centuries after the Roman occupation ended.

Much has been lost to the ravages of acid soil, ploughing and sheer length of time; but fragments that do survive can offer us intriguing glimpses of the past. Perhaps what has survived at this site, to be found in the 21st century, was protected by the Goddess, or by some other guardian watching over it? During preparations on the morning of the geophysical survey, the two-legged workers in the field were quietly observed by a bright-eyed four-legged figure: a fox, who did not object to having his photo taken … perhaps the guardian of this site?