It’s a Peach of an Exhibition

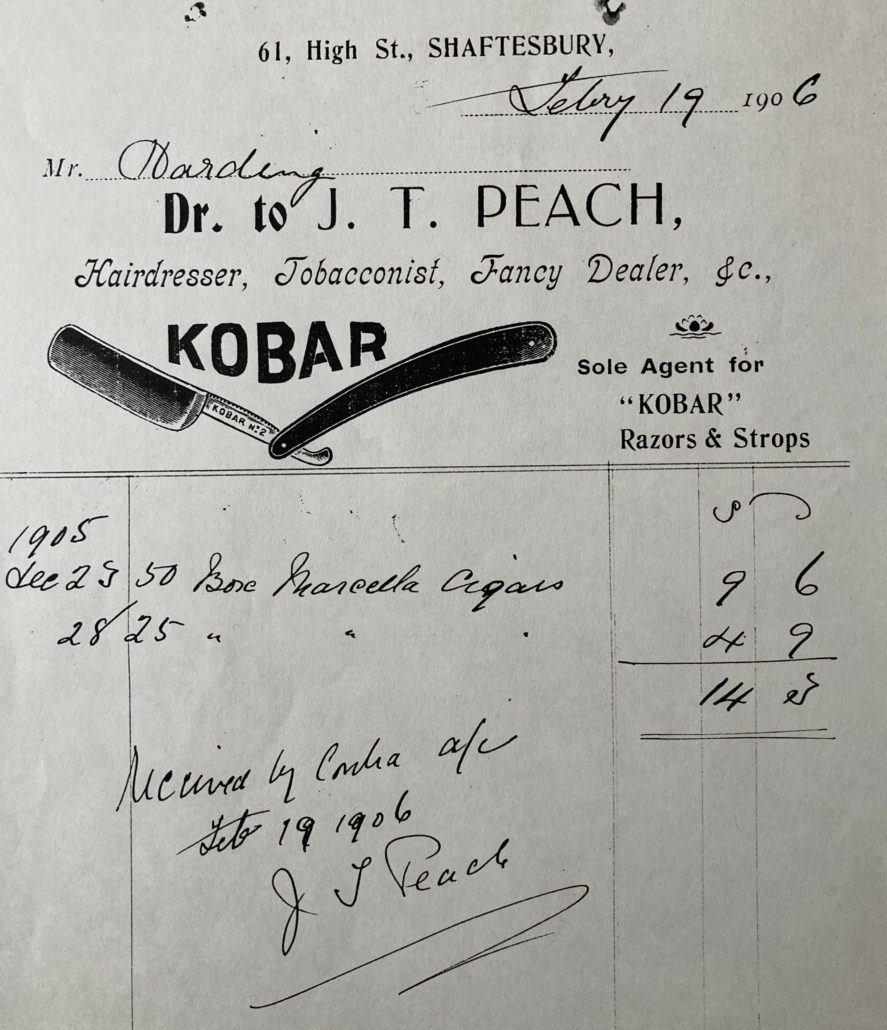

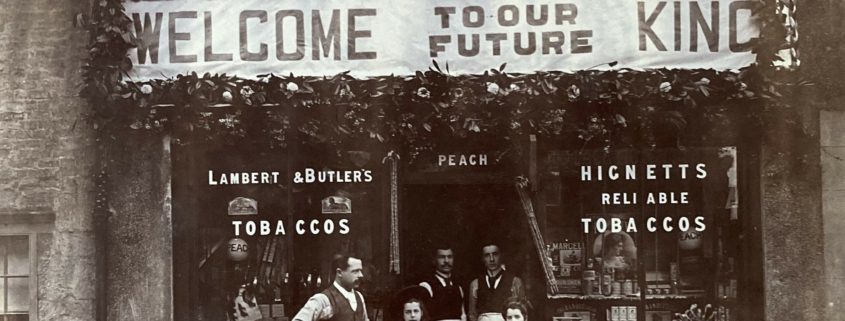

For the new season beginning 01 April 2023 Gold Hill Museum offers an intriguing temporary exhibition on the contribution to the Shaftesbury community of the Peach family. John T Peach (1866-1941) was the eldest son of Walter (1832-1901) and in the coronation year 1902 he and his family were living “above the shop” at 61 High Street, Shaftesbury, where John ran a thriving hairdressing and tobacconist’s business. Edward VII should have been crowned king in June 1902, but underwent emergency surgery for acute appendicitis two days before the ceremony, which was postponed until 09 August. The patriotic decoration of the shop exterior (above) seems appropriate for a coronation, and the photograph has traditionally been assigned to 1902. However, the present writer thinks (and it’s only his opinion) that the photograph was probably taken in October 1899 when Edward made a flying royal visit to Shaftesbury as Prince of Wales. The town had geared itself up for a royal spectacular, with a temporary grandstand built in the High Street outside the Town Hall, and a competition for the best celebratory bunting. In the event, the Prince changed his plans and didn’t even step down from his carriage. More of a Pit Stop than a Royal Visit – Gold Hill Museum

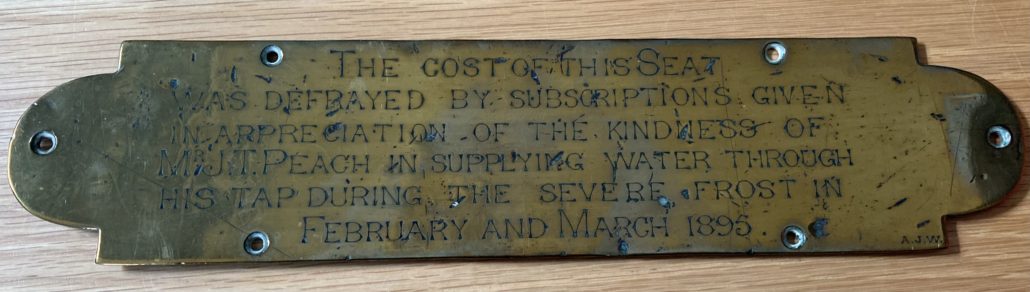

Two of John’s daughters, Hilda (1890-1964) and Margaret Rosina (1892-1978) are visible in the shop doorway, together with two of his brothers, William (1875-1936) and Sidney (1877-1947). Sidney married Flora Cooper in 1901 and moved to Newbury in Gillingham (Dorset), where he too set up as a hairdresser and tobacconist. This tends to confirm that the photograph is from 1899 rather than 1902 (if one of the young men is Sidney.) Sidney’s story can be consulted in a folder alongside the exhibition kindly provided by David Lloyd of Gillingham Local History Society. William also married in 1901, to Elizabeth England, but remained in Shaftesbury working in his brother’s shop. John had moved to the larger premises at 61 (later also incorporating 59) High Street in 1896, from 09 Salisbury Street. The year before his move, he had been left with the only unfrozen water tap in Shaftesbury during the big freeze of February and March 1895.

Archive volunteer and exhibition curator Heather Blake has found a tangible expression of Shastonians’ gratitude to John Peach for his 1895 altruism, in the shape of a brass plaque. John refused to accept any monetary reward, so the proceeds of a collection went towards the provision of a public bench (now gone) in Boyne Mead.

A third daughter, Doris Blanche, was born to John and Susan (nee Davis) Peach in 1902. All three daughters became energetic supporters of the St John Ambulance Brigade and Shaftesbury Carnival, which was a major source of funding for the local Westminster Memorial Hospital in pre-NHS days. John formed the Shaftesbury Hospital League as another means of assisting health care. Hilda’s husband, Sidney Hussey, dealt in coal, corn and general merchandise at 58 High Street, where the St John Ambulance was parked in a yard at the rear of the premises. At Doris’s wedding in 1931, St John Ambulance members formed a guard of honour, having the previous evening given the bride-to-be a handsome oak clock. Her husband, James Hillier, rose to be a regional manager in British Railways engineering. In 1964 he salvaged one of the name-plates from the recently-scrapped steam locomotive “Shaftesbury” and presented it to the town.

The Peach business expanded to include ladies’ hairdressing and the sale of confectionery. The 1935 Kelly’s Directory lists Peach, Jn. Thos. Tobacconist, 61 High St, and Peach, Miss Margaret Rosina, confectioner, 59 High St. John held a policy from the Shaftesbury Plate Glass Mutual Insurance Society, becoming a director of the Society, and keeping its Minute Book in an immaculate hand, as shown in the exhibition. After her father’s death in 1941, Margaret Rosina continued to manage the Peach enterprise.

The heading for this Peach of an Exhibition is “Shopkeepers Who Made A Difference.” Heather has assembled a fascinating variety of artefacts, documents, and photographs, with invaluable help from descendants of John Peach. You can see this display on the first-floor landing outside the Museum Library and Lift. Keep going to the far side of Room 4 Life in the Town. As with all our exhibitions, it’s free.

.